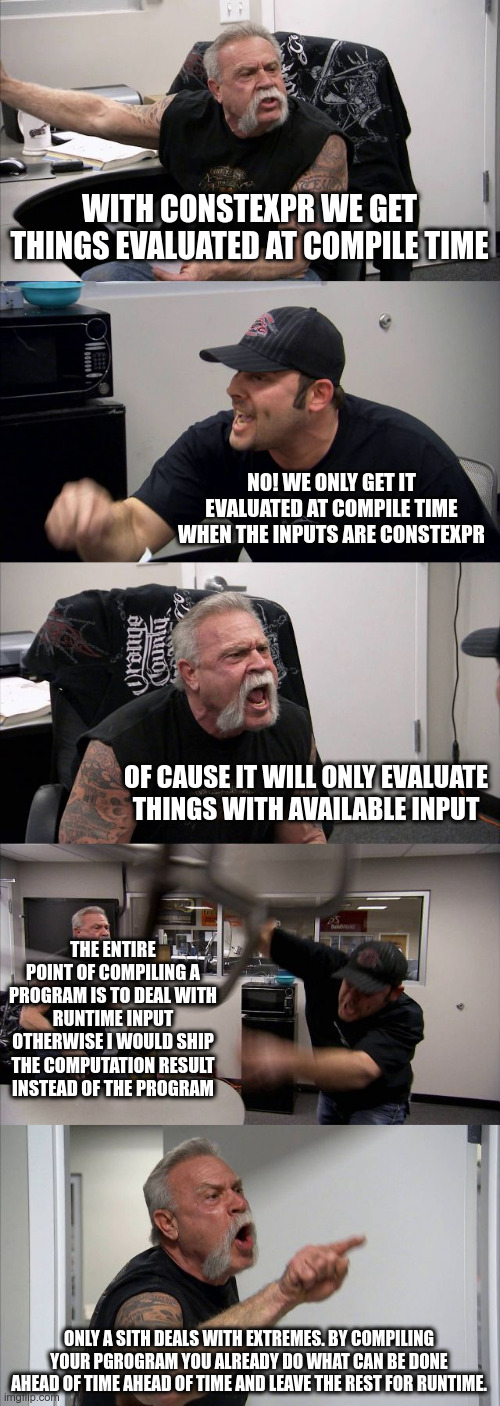

maybe constexpr and consteval shouldn't have been shipped separately

I’m not overly happy with how constexpr hyped around the C++

world. But let’s pack the rant into this little meme and then take the

high ground.

Whoopsie, even a typo in the meme.

Let’s take a step back and look at this program

|

|

As we can see on compiler explorer, the compiler figured out the sum by itself

|

|

you might argue, the output got computed at compile time. BUT if we actually try to use this number at compile time, the compiler doesn’t let us (compiler explorer link)

|

|

<source>:14:22: error: non-type template argument is not a constant expression

14 | std::array<int8_t, some_sum()> a{};

| ^~~~~~~~~~

<source>:14:22: note: non-constexpr function 'some_sum' cannot be used in a constant expression

<source>:5:5: note: declared here

5 | int some_sum() {

| ^

1 error generated.

Compiler returned: 1

Even though the compiler computed the output of some_sum at compile

time, it complains that it’s not a constant expression. In plain

English, I find this a bit contradictory, but in terminology “computed

at compile time” and “constant expression” are not the same

thing. Moreover, the compiler tells us that my program is not well

formed, it’s not compliant with the C++ standard, and I should care

about that: The return value of some_sum only got computed at

compile time because my compiler is smart enough. A less sophisticated

yet standard compliant compiler might not be able to compute

some_sum. This means that my program can’t be given to any compiler

and should therefore be rejected.

You may argue that compilers accept non-compliant code left and right (designated initializers even in C++-17 mode is my favourite) but I guess that’ a different story.

Now that’s where the constexpr keyword comes in handy. Just adding

constexpr to the definition of some_sum solves the issue and we

have a valid program again (compiler explorer

link).

I’ll jump straight to the next issue:

|

|

Here, we have a constexpr function, but the compiler is not able to

use its return value as a template argument. The reason is pretty

clear, the argument to add_five is a runtime variable. In

production-scale code, this becomes less obvious. Once the arguments

to constexpr functions themselves are return values of constexpr

functions, or more complex call chains spread over multiple projects

(add macros, translation units, and templates to the mix), it might

not be visible at all, if a constexpr function gets evaluated at

runtime or compile time. And one might even be in the situation where

all inputs are known at compile time (from a high level of business

logic) but the standard might not consider everything constant expression and the optimizer might even come to a different

conclusion.

That becomes more frustrating, when one writes a constexpr function,

and puts its complexity or run time cost aside with the argument that

it will be evaluated at compile time … but it won’t.

Andreas Fertig covered this in his blog,

too,

and probably better than I did above. The only thing that I don’t like

about the post is that - posted in 2023 - the keyword consteval

should’ve come up.

Whereas constexpr - to me - means “here’s the function, if you want

to use it at compile time, by all means do, but ultimately just use it

whenever you want”, consteval on the other hand is “here’s the

function, and the compiler will make sure that it will be used at

compile time and not accidentially run at runtime”.

And I guess when teaching/learning about constexpr in - say - 2017 -

probably many misunderstandings could’ve just been cleared by

presenting constexpr and consteval along with each other. Should

constexpr been delayed until C++-20? Well, probably not. If one

really wanted a “do this only at compile time”, one could’ve done

template meta programming

|

|

Now FiveAdder ensures that it’s evaluated at compile time, and I

assume we can agree that the consteval keyword on add_five is much

nicer than rewriting everything to template arguments.

Leaves the question: why aren’t functions constexpr by default? If

the keyword anyways only gives us “can be used in constant expressions

when possible”. Honestly, I’m not sure I want to know. Anyways, here

are four more links to Andreas’s blog on the topic

- C++20: a neat trick with consteval

- C++ Insights Episode 53: Mastering C++23: Leveraging if consteval for more constexpr functions

- C++ for embedded systems: constexpr and consteval

- C++ Insights Episode 67: C++23: Why if consteval can make your code better